Understanding the challenge of change

Navigating life's transitions

Here is a story about the challenge of change.

On 8 January 2008, in my 40s, I left my home in London with my pregnant wife to move to her home in Sydney, Australia.

I left behind my city, my close family and my life long friends.

I left behind pretty much everything I’d ever known and everyone I had a shared history with.

I left all my interests (like this and this) and all the things, other than my wife, that I felt closely connected to.

Not long after we arrived in Sydney, my much-loved aunt died.

A few weeks later, after a very difficult birth, my beautiful daughter, Amelia was born.

Not long after that, both my wife and I pretty much fell apart.

So what happened?

The challenge of change

Significant change can be a major challenge. There can be a surprising range and progression of emotions involved.

This can be difficult to manage over the long term, even when the change is ostensibly a positive one.

If you are contemplating change or dealing with change right now, it will help if you have some understanding of how we typically respond to change.

In this and some subsequent posts, I’ll look at some of the change frameworks that I have found useful in coaching people through transitions.

I have to admit that I wish I had been aware of this thinking back in 2008.

Transition and crisis

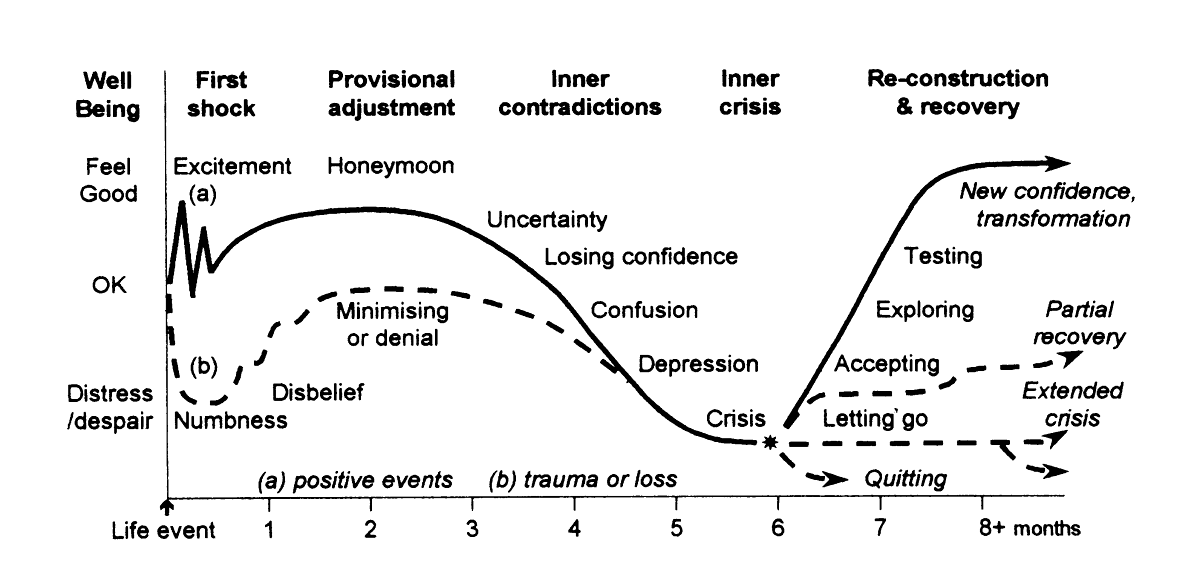

Psychologist Dai Williams provides us with a model of change that seems especially relevant to unexpected or unprepared for change. He points out that these kinds of changes can be incredibly destabilising, regardless of whether, ostensibly, they are positive or negative.

According to Williams there can often be a period of “deep inner crisis” 6 months or so after the change.

These crises can be major turning points if well supported.

But if support is inadequate, they can lead to major psychological breakdown, poor performance, errors of judgement and career or relationship failures (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: The transition cycle – a template for human responses to change, adapted from Hopson and Adamans (1976)

Williams suggests that the following factors are either enablers or inhibitors in the transition process.

Enabling factors in transitions

Economic security – sufficient resources, no debt, stable income, own home, low commitments, multiple-income household.

Emotional security – supportive partner, stable childhood, support networks, openness on emotional and mental health issues.

Health – good physical fitness, prudent lifestyle, quality time for leisure.

Prior transition skills – positive transition experiences in the past

Clear goals – purposeful and values led process.

Supportive operating environment (work or family) – high respect / low control culture, good morale, clear role and contract terms, life-work boundaries respected.

Transition support – practical support, life/career planning, tolerance, dignity, valuing the past, freedom/recognition for new ideas

Inhibiting factors in transitions

Economic insecurity – low income, debt, high financial commitments, fear of job loss.

Emotional insecurity – no partner, few friends, dependent relatives, secret grief (lost lover or child), sense of guilt, unresolved issues or regrets, multiple transitions, anxiety over being diagnosed mentally ill.

Health – chronic or undiagnosed conditions, low fitness, fatigue, lifestyle.

Hostile operating environments (work or family) – work overload, unrealistic demands, insufficient resources, abuse of work/life boundary Low respect/high control culture.

Poor transition management – no support, no preparation for change, unrealistic time scales. No monitoring of key issues pre-crisis. No opportunity for fresh insights. Past achievements ignored or rubbished.

When I think back to the period around our move from the U.K to Australia, I can see now that for us many of the key enabling factors were missing. We lacked economic security, prior transitions skills, clear goals, supportive environments and transition support.

We also experienced a number of the inhibiting factors – emotional insecurity, poor health, hostile environments, poor transition management.

In fact, even after 10 years, I never felt settled living in Australia. In the end, we moved back to the UK. This meant we all - but my wife and 2 daughters especially - had to navigate another major transition. And that has not been easy for them.

As I reflect now on the challenge of change in the light of these experiences and Williams transition model, it is not all surprising how it can be hard to come through transitions.

My experience suggests that emergence from the crisis point is critical. And, when we moved to Australia, my emergence was not entirely successful. In the terms of Figure 1 above, I’d suggest I only made a partial recovery.

Williams writes that emergence from the transition cycle:

is facilitated by valuing the past and still viable beliefs before letting go of obsolete concepts, expectations and behaviours …There can be a rapid, spontaneous breakout from the crisis phase – a defining moment or catharsis that triggers this process. Once begun, the restructuring or recovery process can occur within a few weeks. It liberates creativity, confidence, optimism, a search for new meanings and a Gestalt type quest for a fully integrated view of the new reality. To see a person transforming their life in the recovery phase is like watching a flower open.

The critical point that I take from this, is the letting go.

It seems that what we need in these kinds of transition processes is a way to hang on to what is valued from the past, without allowing it to overshadow the present.

If we cling too tightly to what has gone before, we risk preventing the future from ever beginning.

Focusing on mindfulness practices can help. This reflection from Tara Brach proved especially useful for me.

Here are the key takeaways from my experience:

Awareness is crucial: Understanding the typical responses to change and the factors that influence our ability to cope can help us navigate transitions more effectively.

Support matters: Having a strong support system and the right enabling factors in place can make a significant difference in how we navigate periods of change.

Crisis can lead to growth: While challenging, the crisis phase of transition can be a turning point, leading to personal growth and new perspectives if managed well.

Letting go is essential: One of the most critical aspects of successful transition is learning to let go of what no longer serves us, while still valuing our past experiences.

Mindfulness can help: Practices like mindfulness can be powerful tools in helping us navigate the emotional landscape of change and transition.

Recovery is a process: Emerging from a period of significant change is not always quick or linear. It's okay if recovery takes time and happens in stages.

Self-reflection is valuable: Taking the time to reflect on our experiences of change in a productive way can provide insights that help us better prepare for future transitions.

References

Hopson, B. & Adams, J. (1976) Transition – Understanding and managing personal change.

Williams, D. (1999) Life events and career change: transition psychology in practice

Williams Futures, Vol.31 (6) August 1999, 609-616

Related Posts

My other posts on change are all here.